[I suppose it’s only natural that you start thinking about treasure hoards around this time of the year. And lost or hidden treasures seem especially apt after spending a day putting piles of wrapping paper into the bin,, only to have to take it all back out while searching to see if you accidentally threw out something that the kids can’t find.]

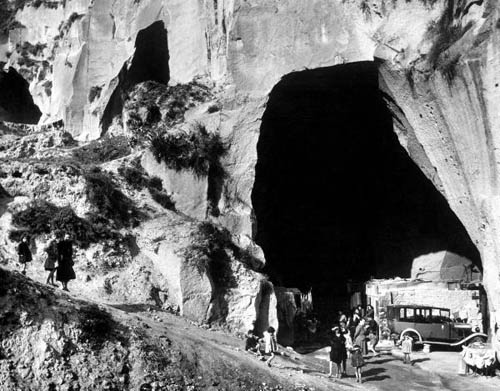

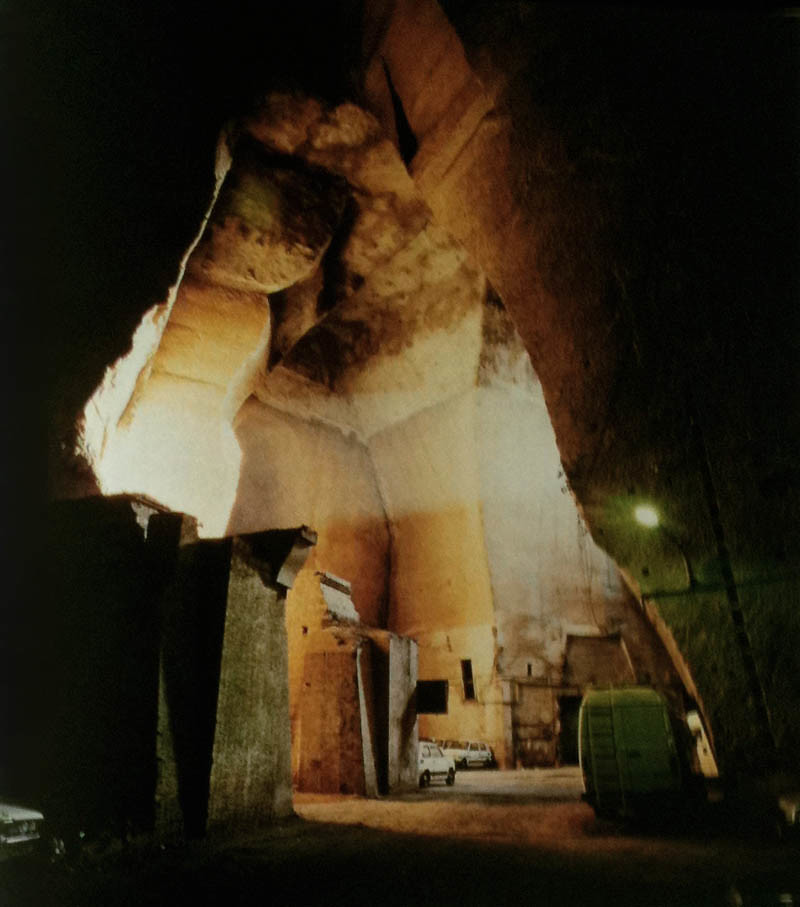

The Wash is a large square bay and estuary of four rivers (the Witham, Welland, Nene, and Great Ouse) in East Anglia. The land around about is largely broad, flat moors and fens, much of which has been reclaimed and turned to farmland over the centuries, and the Wash itself is quite shallow with many large sandbanks. That very flat terrain gives the area a large tidal variation, and in the past many of the inland areas were prone to flooding with the tides; these sodden areas also hide many large patches of quicksand. All of which was a factor when King John lost the crown jewels.

John of England hadn’t been the most successful or popular of kings. Born in 1167 as the youngest son of Henry II, under ordinary circumstances he would have expected no inheritance from his father. But in the 12th century, and for the royal families in particular, ordinary circumstances were far from the rule. After a period of machinations and rebellions from his brothers against his father, in which John had a reputation for plotting both with and against his brothers, his brother Richard became king in 1189. Richard joined the Third Crusade in 1190 and spent the next four years warring in the holy lands. In his absence, John attempted to overthrow his chancellor, a period that became part of the story of Robin Hood.

John ascended to the throne in 1199, when his brother died without an heir, and set about earning himself the title “Bad King John”. After a series of military failures that lost the English kings their territories in France (earning him the nicknames “John Lackland” and “John Softsword” among the nobles), he had to raise taxes in England to make up for the lost French income. He further angered the barons by his treatment of them, especially by the rumours that he was seducing their wives and daughters. He argued with the pope and was not only excommunicated but had the entire English church cut off until he relented.

The barons decided that enough was enough and obliged John to sign the Magna Carta. John attempted to wriggle out of it and prompted a war with his own barons that saw a French army land in England in support of the rebel barons. In late 1216, John was in King’s Lynn (then Bishop’s Lynn) on the banks of the Wash. He was seeking a quick exit from the area without entering the rebel strongholds in East Anglia, and so attempted to head directly east, crossing several of the rivers in the area. His baggage trains were too slow, the tide changes before they are done and the rivers start to surge. Then, as Charles Dickens wrote:

… looking back from the shore when he was safe, he [the king] saw the roaring water sweep down in a torrent, overturn the waggons, horses, and men, that carried his treasure, and engulf them in a raging whirlpool from which nothing could be delivered.

Among that train was supposedly the English crown jewels, including those that were inherited from his grandmother, the Empress of Germany. John proceeded on to Swineshead Abbey, with his monarchy in now serious financial trouble. He contracted dysentery and ultimately died only a few days later. The treasures with the baggage train have never been recovered.

Now, there are many questions left open in this story. The first is, where exactly did the incident happen? The terrain in the area is very different now than it was 800 years ago. The boundaries of the Wash are different, the rivers have changed course, human intervention has both raised and lowered areas. If the treasures are still there, then they could be buried under 20 or 30 feet of silt now.

The other is, were the crown jewels really lost at all? It seems strange to think that John would have been dragging them around the country, but he had given himself plenty of reasons to be suspicious of people. More interesting is that the most contemporary reports about the incident don’t mention the crown jewels; they certainly say that there was a lot of valuable cargo lost, but they don’t mention those jewels in particular.

The jewels certainly went missing: in John’s reign he ordered an inventory of all the royal possessions (the Rolls), but when another inventory was taken for his successor (Henry III) in 1220 much of it is absent. There were rumours that John had used the jewels to secure a loan, or that they had been sold, to pay for the war and then fabricated the story of the lost baggage. Of course, that’s rather typical of the stories that people do tell, of unpopular kings. There was also a rumour that the monks of Swineshead Abbey had poisoned the king, perhaps then to have stolen the jewels and the concocted lost baggage train story, or perhaps just as further machinations in the scheming of the day?

There are lots of great things to pick up out of this story. Apart from the lost treasure itself, there is the mystery story of the plotting treacherous king undone by treachery himself. There is the detail of the royal inventories: what if the characters are tasked to find items that are missing from them? Perhaps there is a coronation or marriage that has to be delayed until they can be found – admitting they are lost would be either too embarrassing or would cast doubt on the legitimacy of the throne. It wouldn’t have to be a king either, perhaps a baron could be in a similar situation? They will delay as long as they can, but they can’t keep a lid on the situation forever.

Finally, there is the Wash itself and the surrounding lands. A terrain which is something of an adversary itself, prone to sudden flooding, home to quicksands, and hiding sandbars to make navigating by boat dangerous too. And perhaps also the site of a lost, priceless treasure.

The head and tail of a centipede; photo from

The head and tail of a centipede; photo from

Devils tempt a dying man with crowns, via

Devils tempt a dying man with crowns, via